Cervical Cancer Screening Technologies With Pap and HPV - CAM 314

Description

Cervical cancer screening detects cervical precancerous lesions and cancer through cytology, human papillomavirus (HPV) testing, and if needed, colposcopy.1 The principal screening test to detect cancer in asymptomatic individuals with a cervix is the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear. It involves cells being scraped from the cervix during a pelvic examination and spread onto a slide. The slide is then sent to an accredited laboratory to be stained, observed, and interpreted.2

Human papilloma virus (HPV) has been associated with development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, and FDA-approved HPV tests detecting the presence of viral DNA from high-risk strains have been developed and validated as an adjunct primary cancer screening method.2

For additional information on testing for HPV, please refer to CAM 209-Diagnostic Testing of Common Sexually Transmitted Infections.

Terms such as male and female are used when necessary to refer to sex assigned at birth.

Regulatory Status

Several liquid based preparations have received premarket approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). For example, in May 1996, "ThinPrep® Pap Test" was approved by the FDA through the premarket approval process for use in collecting and preparing cervical cytology specimens for Pap stain-based screening for cervical cancer.

Several automated screening systems have received premarket approval through FDA. For example, in September 1995, AutoPap® Automatic Pap Screener, now FocalPointTM, was approved by the FDA through the premarket approval process for use in initial screening of cervical cytology slides. The device is intended to be used on both conventionally prepared and prepstain system cervical cytology studies.

In March 2003, test kit digene® HPV test was approved by the FDA through premarket approval process for use in diagnostic testing for the qualitative detection of DNA from 13 high-risk papillomavirus types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) in cervical specimens.

In March 2009, test kit Cervista® HPV HR was approved by the FDA through the premarket approval process for use in diagnostic testing for the qualitative detection of DNA from 14 high-risk papillomavirus (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) in cervical specimens.

Several organizations and professional societies have developed guidelines or recommendations for cervical cancer screening, to optimize early detection and to reduce false positives. The focus has been on test selection and frequency of testing, as well as follow-up testing for abnormal results.

In 2012, the American Cancer Society (ACS), American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), and American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) issued joint guidelines regarding cervical cancer screening.1 The focus areas of their recommendations were listed as:

- Optimal cytology screening intervals

- Screening strategies for women 30 years and older

- Management of discordant combinations of cytology and HPV results (e.g., HPV positive, cytology negative and HPV negative, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance [ASCUS] results)

- Exiting women from screening

- Impact of HPV vaccination on future screening practices

- Potential utility of molecular screening (Specifically, HPV testing for primary screening was assessed as a potential future strategy.)"

The recommendations are segregated primarily by age group:

- Women under 21 years of age (regardless of sexual activity or other high risk behavior), or over 65 years of age, or who have had surgical removal of the cervix, should not receive cervical cancer screening tests, unless there is a compelling medical reason to do so.

- Women 21 – 29 years of age should have screening with cervical cytology only, at a frequency of every 3 years. Cytology results of ASCUS in this group should be followed up by high risk HPV testing for determination of the appropriate follow-up.

- Women 30 – 65 years of age should preferably have co-testing with cervical cytology plus high-risk HPV testing every five years, or testing with cervical cytology alone every 3 years (deemed acceptable).

- Individuals who have been vaccinated against high risk HPV types should follow the testing recommendations for their age group.

- HPV testing alone (without cytology) is not recommended as a first tier cervical cancer screening test in any age group.

Also in 2014, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued an update to its 2012 recommendation statement on cervical cancer screening.2 The criteria in the USPSTF recommendations are consistent with those listed above for the ACS, ASCCP, ASCP recommendation, except that the USPSTF does not indicate a preference for co-testing with Pap and HPV every 5 years over testing with Pap alone every 3 years, for women ages 30 – 65.

The USPSTF report notes that women have historically used the annual Pap test visit to discuss other health concerns with their health care provider. They urge that, "Individuals, clinicians, and health systems should seek effective ways to facilitate the receipt of recommended preventive services at intervals that are beneficial to the patient. Efforts should also be made to ensure that individuals are able to seek care for additional health concerns as they present."

Similarly, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a Practice Bulletin in 2012, which aligns with the recommendations above.4 Members of ACOG participated in the development of both sets of guidelines.

Referral for cancer genetic consultation is recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors for individuals with a personal or family history indicative of a hereditary form of cancer.

Policy

Application of coverage criteria is dependent upon an individual’s benefit coverage at the time of the request.

The criteria below are based on recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, The National Cancer Institute, NCCN, The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, The American Cancer Society, The American Society for Clinical Pathology, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Within these coverage criteria, “individual(s)” is specific to individuals with a cervix.

- For immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals, any one of the following cervical cancer screening techniques is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY:

- Annual cervical cytology testing for individuals of all ages.

- Co-testing (cervical cytology and high-risk HPV [hr-HPV] testing) once every 3 years for individuals 30 years of age or older.

- For individuals 21 to 29 years of age, cervical cancer screening once every 3 years using conventional or liquid-based Papanicolaou (Pap) smears is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For individuals 30 to 65 years of age, any one of the following cervical cancer screening techniques is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY:

- Conventional or liquid-based Pap smear once every 3 years.

- Cervical cancer screening using the hr-HPV test alone once every 5 years.

- Co-testing (cytology with concurrent hr-HPV testing) once every 5 years.

- For individuals who are over 65 years of age and who are considered high-risk (individuals with a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer, individuals with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES)), cervical cancer screening at the frequency described in coverage criterion 3 is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For individuals who are pooled hr-HPV positive, nucleic acid testing for high-risk strains HPV-16 and HPV-18 is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For individuals 65 years of age or younger, annual cervical cancer screening by Pap smear or hr-HPV testing is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY in any of the following situations:

- For individuals who had a previous cervical cancer screen with an abnormal cytology result and/or who was positive for HPV.

- For individuals at high-risk for cervical cancer (organ transplant, exposure to the drug DES).

- For all situations not addressed above, cervical cancer screening (i.e., cervical cytology, hr-HPV testing) for individuals less than 21 years of age is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For individuals over 65 years of age who are not immunocompromised, immunosuppressed, or who are not considered high-risk for developing cervical cancer (i.e., had abnormal cytology or previously tested positive for hr-HPV), routine cervical cancer screening is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For individuals who have undergone surgical removal of the uterus and cervix and who have no history of cervical cancer or precancer, cervical cancer screening (at any age) is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- Testing for low-risk HPV is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

The following does not meet coverage criteria due to a lack of available published scientific literature confirming that the test(s) is/are required and beneficial for the diagnosis and treatment of an individual’s illness.

- For cervical cancer screening, all other technologies not discussed above is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

Table of Terminology

| Term |

Definition |

| ACOG |

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| ACS |

American Cancer Society |

| AIS |

Adenocarcinoma in situ |

| ASCCP |

American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology |

| ASC-H |

Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| ASCO |

American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| ASCP |

American Society of Clinical pathology |

| ASCUS |

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance |

| CIN (2, 3, 3+) |

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (Grade 2, 3, 3+) |

| CLIA ’88 |

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 |

| CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| DES |

Diethylstilbestrol |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| EASC |

European AIDS Clinical Society |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| GvHD |

Graft versus/against the host disease |

| HGSIL/HSIL |

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| HHS |

Health and Human Services |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HPV |

Human papillomavirus infection |

| hr-HPV | High-risk HPV |

| HSCT |

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| IPD |

Individual participant data |

| JAMA |

Journal of the American Medical Association |

| LDTs |

Laboratory developed tests |

| LEEP |

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure |

| LGSIL/LSIL |

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| mRNA |

Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NAAT |

Nucleic acid amplification test |

| NCCN |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NCI |

National Cancer Institute |

| Pap |

Papanicolaou |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| SGO |

Society of Gynecologic Oncology |

| STIs |

Sexually transmitted infections |

| USPSTF |

United States Preventive Services Task Force |

| VAT |

Visual assessment for treatment |

| VIA |

Visual inspection with acetic acid |

| VIAC |

Visual inspection with acetic acid and digital cervicography |

Rationale

The American Cancer Society estimates that 13,620 new cases of cervical cancer will be diagnosed in 2025 and approximately 4,320 of these individuals will die from the disease.3 To screen for cervical cancer, a Papanicolaou (Pap) test or human papillomavirus (HPV) test is performed. Co-testing with both is also a common clinical practice. To obtain the cell sample for cytology, cells are scraped from both the ectocervix (external surface) and endocervix (cervical canal) during a speculum exam to evaluate the squamocolumnar junction where most neoplasia occur.

Cytological examination can be performed as either a traditional Pap smear where the swab is rolled directly on the slide for observation or as a liquid-based thin layer cytology examination where the swab is swirled in a liquid solution so that the free cells can be trapped and plated as a monolayer on the glass slide. One advantage of the liquid cytology assay is that the same sample can be used for HPV testing whereas a traditional Pap smear requires a second sample to be taken. HPV testing is typically a nucleic acid-based assay that checks for the presence of high-risk types of HPV, especially types 16 and 18. HPV testing can be performed on samples obtained during a cervical exam; furthermore, testing can be performed on samples obtained from a tampon, Dacron or cotton swab, cytobrush, or cervicovaginal lavage.2

Cervical cancer screening recommendations for average-risk individuals generally fall into categories based on an individual’s age:

- Age < 21 – It is suggested to not screen for cervical cancer in asymptomatic and immunocompetent patients (as observational studies show a low incidence and benefits may outweigh the harms of false positives).

- Age 21 to 29 – In average patients that are asymptomatic and immunocompetent, the age at which to initiate screening is contested and the ideal testing method varies by guideline. Opinions for expert groups also vary. A preference for cytology (rather than HPV testing) for this subgroup is based on a meta-analysis of randomized trials that revealed higher false positive rates for HPV testing.

- Age 30 to 65 – It is recommended that cervical cancer screening continues in all immunocompetent and asymptomatic individuals with a cervix. The methods range from primary HPV testing every 5 years to co-testing (Pap and HPV testing) every five years; or a Pap test alone every three years.

- Age >65 years – The decision to halt cervical cancer screening in asymptomatic and immunocompetent patients can depend on factors such as prior screening results, life expectancy, and patient preference, but it is suggested to discontinue screening for this subgroup if there has been adequate prior screening.

The above recommendations do not account for special populations such as patients with HIV, immunosuppression, and in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol.5 These populations are at greater risk for developing cervical cancer.4

The following are the initial screening recommendations for individuals with HIV:6

- Initial screening for HIV should occur when HIV is first diagnosed (but at no earlier than 21 years of age).

- Age 21 to 29 – Cervical cytology is the preferred method for screening.

- Age 30 years or older – Cervical cytology or co-testing are both appropriate. However, the use of HPV testing alone (i.e., without co-testing) is NOT recommended for this subgroup.

For patients with HIV in whom initial screening is normal, subsequent screening is categorized based upon method (i.e., cervical cytology, co-testing, colposcopy):6

- Cervical cytology: Those screened with cervical cytology (patients 21 to 29 years and those 30 and older) should have cervical cytology performed every 12 months for a total of three years. If results of three consecutive cytology tests are normal, a follow-up test can occur every three years.

- Co-testing: Those screened with co-testing (30 years and older) should have this co-testing occur every three years.

- Colposcopy: Should not be performed routinely at follow-up visits.

- Screening in the HIV population should occur throughout a patient’s lifetime and should not stop at 65 years old (contrasted against the general average patient recommendations, which suggest discontinuing at 65 years old).

At-home collection kits have recently shown success in screening for cervical cancer by detecting high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) known to cause nearly all cervical cancers. Teal Health developed the Teal Wand, the first FDA-authorized at-home self-collection device for cervical cancer screening. The device allows individuals to collect a vaginal sample at-home, which is tested using a PCR-based HPV assay.7 The Teal Wand was validated in a clinical trial of 599 participants.8 Self-collected samples demonstrated a 95.2% positive agreement and a 90.0% negative agreement for detecting high-risk HPV compared with clinician-collected samples. The clinical sensitivity for detecting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia was 95.8%, equivalent to clinician-collected samples.8 The Teal Wand provides a non-invasive, patient-friendly alternative to in-clinic cervical cancer screening, with diagnostic accuracy comparable to standard methods. It follows American Cancer Society (ACS) screening guidelines and is recommended for individuals aged 25–65 years with a cervix (those who have not had a full hysterectomy). Regular screening is advised even for individuals who have received the HPV vaccine.7

Analytical Validity

A study by Marchand, et al. (2005) explored the optimal collection technique for Pap testing. Their study occurred in two different cytology labs and 128 clinicians participated in the study over the course of one year. The authors discovered that in conventional Pap testing the sequence of collection—the Cytobrush for the endocervix and the spatula for the ectocervix—had no effect on the quality of the assay. Further, 47% of the clinicians who had high levels of absent endocervical cells on their samples used the Cytobrush method alone. The authors concluded, “The combination of the Cytobrush (endocervix) and spatula (ectocervix) is superior for a quality Pap smear. The sequence of collection was not important in conventional Pap smears. The broom alone performs poorly.”9

Urine-based HPV DNA testing as a screening tool would be a less invasive method than cervical examinations and swabs. A study by Mendez, et al. (2014) using both urine samples and cervical swabs from 52 patients, however, showed that there was only 76% agreement between the two methodologies. The urine testing correctly identified 100% of the uninfected individuals but only 65% of the infected as compared to the cervical swab controls.10 An extensive meta-analysis of 14 different studies using urinary testing, on the other hand, reported an 87% sensitivity and 94% specificity of the urine-based methodology for all strains of HPV, but the sensitivity for high-risk strains alone was only 77%. The specificity for the high-risk strains alone was reported to be higher at 98%. “The major limitations of this review are the lack of a strictly uniform method for the detection of HPV in urine and the variation in accuracy between individual studies. Testing urine for HPV seems to have good accuracy for the detection of cervical HPV and testing first void urine samples is more accurate than random or midstream sampling. When cervical HPV detection is considered difficult in certain subgroups, urine testing should be regarded as an acceptable alternative.”11

Clinical Utility and Validity

The National Cancer Institute reports that “Regular Pap screening decreases cervix cancer incidence and mortality by at least 80%.”12 They also note that Pap testing can result in the possibility of additional diagnostic testing, especially in younger individuals, when unwarranted, especially in cases of possible low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSILs); however, even though 50% of individuals undergoing Pap testing required additional, follow-up diagnostic procedures, only 5% were treated for LSILs. The NCI also reports that “HPV-based screening provides 60% to 70% greater protection against invasive cervical carcinoma, compared with cytology.”12

A study by Sabeena, et al. (2019) measured the utility of urine-based sampling for cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings. The researchers compared 114 samples to determine the accuracy of HPV detection (by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)) in paired cervical and urine samples. Samples were taken from patients previously diagnosed with cervical cancer through histological methods. Of the 114 samples, “HPV DNA was tested positive in cervical samples of 89 (78.1%) and urine samples of 55 (48.2%) patients. The agreement between the two sampling methods was 66.7%.”13 HPV detection in urine samples had a sensitivity of 59.6% and a specificity of 92%. The authors concluded, “Even though not acceptable as an HPV DNA screening tool due to low sensitivity, the urine sampling method is inexpensive and more socially acceptable for large epidemiological surveys in developing countries to estimate the burden.”13

Cervical cancer guidelines published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network state that, although the rates of both incidence and mortality of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix have been declining over the last thirty years, “adenocarcinoma of the cervix has increased over the past three decades, probably because cervical cytologic screening methods are less effective for adenocarcinoma.”14 A study in the United Kingdom supports this increase in adenocarcinoma findings because the risk-reduction associated with three yearly screenings was reduced by 75% for squamous carcinoma and 83% for adenosquamous carcinoma, but adenocarcinoma was reduced only by 43%.15 Another extensive study of more than 900,000 individuals in Sweden showed that PCR-based HPV testing for the high-risk types 16 and 18 is better at predicting the risk of both in situ and invasive adenocarcinoma. The authors conclude, “infections with HPV 16 and 18 are detectable up to at least 14 years before diagnosis of cervical adenocarcinoma. Our data provide prospective evidence that the association of HPV 16/18 with cervical adenocarcinoma is strong and causal.”16

A report by Chen, et al. (2011) reviewed HPV testing and the risk of the development of cervical cancer. Of the 11,923 individuals participating in the study, 86% of those who tested positive for HPV did not develop cervical cancer within ten years. The authors concluded, “HPV negativity was associated with a very low long-term risk of cervical cancer. Persistent detection of HPV among cytologically normal [individuals] greatly increased risk. Thus, it is useful to perform repeated HPV testing following an initial positive test.”17

In 2018, the results of a multi-year cervical cancer screening trial (FOCAL) were published. This randomized clinical trial tested the use of HPV testing alone for detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 3 or worse (CIN3+). More than 19,000 individuals participated in the study—split between the intervention group (HPV testing alone) and the control group (liquid-based cytology). Among individuals who underwent cervical cancer screening, the use of primary HPV testing as compared with cytology testing resulted in a significantly lower likelihood of CIN3+ at 48 months. “Further research is needed to understand long-term clinical outcomes as well as cost-effectiveness.”18 In a commentary concerning the findings of this trial, the author noted that “multiple randomized trials have shown that primary HPV screening linked to subsequent identification and treatment of cervical precancer is more effective than Pap testing in reducing the incidence of cervical cancer and precancer, at the cost of lower specificity and more false-negative subsequent colposcopic assessments.”19 The author did not address the limitations of the FOCAL study, including that the study concluded prior to seeing what effects, if any, those vaccinated against HPV 16 and HPV 18 would have since the adolescents vaccinated upon FDA approval of the vaccine would not have necessarily been included within the study. They also state that a limitation of the FOCAL trial is “the use of a pooled HPV test for screening, incorporating all carcinogenic HPV types in a single positive or negative result.”19

Melnikow, et al. (2018) performed a review for the USPSTF regarding cervical cancer screening through high-risk (hr) HPV testing. The authors reviewed the following studies: “8 randomized clinical trials (n = 410556), 5 cohort studies (n = 402615), and one individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis (n = 176464).” Primary hr-HPV testing was found to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ at an increased rate (relative risk rate ranging from 1.61 to 7.46) in round 1 screening. False positive rates for primary hr-HPV testing ranged from 6.6% to 7.4%, compared with 2.6% to 6.5% for cytology, whereas in cotesting, false-positives ranged from 5.8% to 19.9% in the first round of screening, compared with 2.6% to 10.9% for cytology. Overall, the authors concluded that “primary hrHPV screening detected higher rates of CIN 3+ at first-round screening compared with cytology. Cotesting trials did not show initial increased CIN 3+ detection.”20

Bonde, et al. (2020) performed a systematic review on the clinical utility of HPV genotyping as a form of cervical cancer screening. Through 16 studies, the researchers concluded that “HPV genotyping can refine clinical management” for individuals “screened through the primary HPV paradigm and the co-testing paradigm by stratifying genotype-specific results and thereby assign those at highest risk for cervical disease to further testing (i.e., colposcopy) or treatment, while designating those with lowest risk to retesting at a shortened interval.” After deeming low-risk of bias, the review also stated “the overall quality of evidence for CIN 3 or worse risk with negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancies or low-grade squamous intraepithelial cytology was assessed as moderate; that with atypical squamous cells-undetermined significance and "all cytology" was assessed as high… Human papillomavirus genotyping discriminated risk of CIN 3 or worse to a clinically significant degree, regardless of cytology result.”21

Between 2010 and 2019, Pry, et al. (2021) reviewed 204,225 results from 183,165 study participants across 11 government health facilities in Lusaka, Zambia, as part of the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in Zambia (CCPPZ). By examining precancerous lesions via visual inspection with acetic acid and digital cervicography (VIAC), they were able to show that the highest odds for screening positive are among individuals aged 20–29 years and that individuals “in the 30–39 years age group had the highest proportion of positive screening results (11·3%) among those with age recorded”; interestingly, however, those “who were HIV-positive and younger than 20 years had more than three times the predictive probability (18·4, 95% CI 9·56–27·32) for being positive compared with [individuals] who were HIV-negative in the same age group (predictive probability 5·5%, 95% CI 3·2–7·8).”22 But while the high proportion of the screen positivity in individuals younger than 20 years old may suggest that individuals “with HIV have earlier disease progression” and that these individuals “should be engaged in screening at a younger age”, these data could be the result of “some misalignment between screening test positivity and neoplastic lesions, as visually, cervicitis and other benign cervical lesions could be mistaken for precancerous disease” or even simply the inherent weaknesses in the test accuracy of the VIAC method (“sensitivity from 25% (95% CI 7–59) to 82% (66–95) and specificity from 74% (64–82) to 83% (77–87)”), warranting further examination.22

Many guidelines call for the cessation of cervical cancer screening after the age of 65; however, Dilley, et al. (2021) argues for a reevaluation of recommendations of this ilk, given that 20% of new cervical cancers occur in this group. Moreover, elderly individuals with a cervix are not only more likely to be diagnosed with late stage cancer, but also receive commensurately worse outcomes and higher mortality rates. The authors point to the use of theoretical modelling and expert opinion as leading drivers of misconceptions about cervical screening harm in older individuals, specifying that while many of the models seek to minimize the harms and costs associated with increased colposcopies, they are remiss in their consideration of the costs and benefits of “the treatment of advanced cancer, such as cold knife conization, radical hysterectomy, pelvic radiation therapy and chemotherapy” and in their interpretation of exiguous data on the benefits and harms of screening after 65. Furthermore, though the existing guidelines suggest that “the guidelines account for the importance of adequate prior screening before cessation of screening,” as the majority of cervical cancer cases are diagnosed in individuals who have not been adequately screened, the authors counter that studies have shown that only 25–50% of individuals diagnosed with cervical cancer had “adequate prior screening” before their cancer diagnosis, which will only be further exacerbated as the population continues to age.23

Qin, et al. (2023) studied annual trends in cervical cancer screening-associated services in average-risk women 65 years or older with adequate prior screening. The US Preventative Services Task Force recommends against cervical cancer screening for women 65 years or older with adequate prior screening. Data was collected between 1999 and 2019 from over 15 million (N=15323635) women between the ages of 65 and 114 with Medicare free-for-service coverage. “From 1999 to 2019, the percentage of women who received at least one cytology or HPV test decreased from 18.9% (2.9 million women) in 1999 to 8.5% (1.3 million women) in 2019, a reduction of 55.3%; use rates of colposcopy and cervical procedures decreased 43.2% and 64.4%, respectively.” Further, “the total Medicare expenditure for all services rendered in 2019 was about $83.5 million.” The authors concluded that “while annual use of cervical cancer screening-associated services in the Medicare fee-for-service population older than 65 years has decreased during the last two decades, more than 1.3 million women received these services in 2019 at substantial costs.”24

Winer, et al. (2023) studied the effectiveness of direct-mail and opt-in approaches for offering HPV self-sampling kits. The kits were offered, by mail or opt-in, to females between the ages of 30 and 64 who had been previously screened, at least three months prior, and were due for their next screening. A total of 31,355 participants were included. Participants were classified in three groups: those due for screening, those overdue for screening, or individuals with unknown history of screening. Withing each group, individuals were randomly assigned to receive usual care, education (usual care plus educational materials about screening), direct-mail (usual care, educational materials, and a mailed self-sampling kit), or opt-in (usual care, education, and the option to request a kit). In individuals due for screening, screening completion was 14.1% higher in the direct-mail group than the education group, and 3.5% higher in the opt-in group than the education group. In individuals overdue for screening, screening completion was 16.9% higher in the direct-mail group than the education group. In individuals with unknown history, screening was 2.2% higher in the opt-in group than the education group. The authors concluded that “within a US health care system, direct-mail self-sampling increased cervical cancer screening by more than 14% in individuals who were due or overdue for cervical cancer screening” and “the opt-in approach minimally increased screening.”25

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

The USPSTF updated their recommendations in 2018. The recommendations are outlined in the table below. The USPSTF changed the recommendation concerning women aged 30-65 to now include the possibility of high-risk HPV testing alone once every five years as a screening. They still allow for the possibility of co-testing every five years or for Pap testing alone every three years.

The USPSTF notes certain risk factors that may increase the risk of cervical cancer, such as “HIV infection, a compromised immune system, in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol, and previous treatment of a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer.” Cytology, primary testing for high-risk HPV alone, or both methods simultaneously may detect the high-risk lesions that are precursors to cervical cancer.26

The USPSTF Summary of Recommendations and Evidence:26

| Population |

Recommendation |

Grade |

| Women 21 to 65 years of age |

For women 21 to 29 years of age, screen for cervical cancer every 3 years with cytology alone. For women 30 to 65 years of age, screen for cervical cancer every 3 years with cytology alone, every 5 years with high-risk (hr) HPV testing alone, or every 5 years with co-testing. |

The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. Offer or provide this service. Grade A |

| Women younger than 21, older than 65, who have had adequate prior screening, or who have had had a hysterectomy |

Do not screen for cervical cancer. |

The USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. Discourage the use of this service. Grade D |

In 2017, “The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of performing screening pelvic examinations in asymptomatic, nonpregnant adult women. (I statement) This statement does not apply to specific disorders for which the USPSTF already recommends screening (i.e., screening for cervical cancer with a Papanicolaou smear, screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia).”

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)

Regarding the diagnosis and workup for cervical cancer, the NCCN states that “The earliest stages of cervical carcinoma may be asymptomatic or associated with a watery vaginal discharge and postcoital bleeding or intermittent spotting. Often these early symptoms are not recognized by the patient. Because of the accessibility of the uterine cervix, cervical cytology or Papanicolaou (Pap) smears and cervical biopsies can usually result in an accurate diagnosis. Cone biopsy (i.e., conization) is recommended if the cervical biopsy is inadequate to define invasiveness or if accurate assessment of microinvasive disease is required… However, cervical cytologic screening methods are less useful for diagnosing adenocarcinoma, because adenocarcinoma in situ affects areas of the cervix that are harder to sample (i.e., endocervical canal)” and that “Workup for these patients with suspicious symptoms includes history and physical examination, complete blood count (CBC, including platelets), and liver and renal function tests.”14

The NCCN also remarked that “persistent HPV infection is the most important factor in the development of cervical cancer. The incidence of cervical cancer appears to be related to the prevalence of HPV in the population…. Screening methods using HPV testing may increase detection of adenocarcinoma,” adducing that “In developed countries, the substantial decline in incidence and mortality of SCC of the cervix is presumed to be the result of effective screening and higher human papillomavirus (HPV)-vaccination coverage, although racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities exist.”14 As such, the NCCN lists chronic, persistent HPV infection along with persistently abnormal Pap smear tests as criteria to be considered for women contemplating hysterectomy.

National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Concerning the use of Pap testing in screening, the NCI recommends: “Based on solid evidence, regular screening for cervical cancer with the Pap test in an appropriate population of women reduces mortality from cervical cancer. The benefits of screening women younger than 21 years are small because of the low prevalence of lesions that will progress to invasive cancer. Screening is not beneficial in women older than 65 years if they have had a recent history of negative test results… Based on solid evidence, regular screening with the Pap test leads to additional diagnostic procedures (e.g., colposcopy) and possible overtreatment for low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSILs). These harms are greatest for younger women, who have a higher prevalence of LSILs, lesions that often regress without treatment. Harms are also increased in younger women because they have a higher rate of false positive results. Excisional procedures to treat preinvasive disease has been associated with increased risk of long-term consequences for fertility and pregnancy.”12

Concerning the use of HPV DNA testing, the NCI states: “Based on solid evidence, screening with an HPV DNA or HPV RNA test detects high-grade cervical dysplasia, a precursor lesion for cervical cancer. Additional clinical trials show that HPV testing is superior to other cervical cancer screening strategies. In April 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved an HPV DNA test that can be used alone for the primary screening of cervical cancer risk in women aged 25 years and older… Based on solid evidence, HPV testing identifies numerous infections that will not lead to cervical dysplasia or cervical cancer. This is especially true in women younger than 30 years, in whom rates of HPV infection may be higher.”12

Concerning cotesting, they recommend: “Based on solid evidence, screening every 5 years with the Pap test and the HPV DNA test (cotesting) in women aged 30 years and older is more sensitive in detecting cervical abnormalities, compared with the Pap test alone. Screening with the Pap test and HPV DNA test reduces the incidence of cervical cancer… Based on solid evidence, HPV and Pap cotesting is associated with more false positives than is the Pap test alone. Abnormal test results can lead to more frequent testing and invasive diagnostic procedures.”12

Regarding screening women without a cervix, they recommend: “Based on solid evidence, screening is not helpful in women who do not have a cervix as a result of a hysterectomy for a benign condition.”12

American Cancer Society (ACS)

The American Cancer Society updated their guidelines for cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk in 2020. Their recommendations are summarized below:

(Adapted from Table 2, Comparison of Current and Previous American Cancer Society (ACS) Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening)5

| Population |

2020 ACS Recommendation |

| Age 21-24 |

No screening |

| Age 25-29 |

HPV test every 5 years (preferred) HPV/Pap cotest every 5 years (acceptable) Pap test every 3 years (acceptable) |

| Age 30-65 |

HPV test every 5 years (preferred) HPV/Pap cotest every 5 years (acceptable) Pap test every 3 years (acceptable) |

| Age 65 and older |

No screening if a series of prior tests were normal |

The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)

The ASCCP published the 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors, which provide valuable information on screening for HPV 16/18 and provide important distinctions in management for an individual identified as being positive for HPV 16/18 as compared to those identified as HPV-negative or HPV of unknown genotype (which refers to both HPV testing that happened without genotyping and HPV testing where genotyping is negative for HPV 16 and 18 but positive for other high-risk HPV types). The following recommendations were provided:

- Regarding recommendations for expedited treatment, the guideline was expanded:

- “Expedited treatment was an option for patients with HSIL cytology in the 2012 guidelines; this guidance is now better defined.

- For non-pregnant patients 25 years or older, expedited treatment, defined as treatment without preceding colposcopic biopsy demonstrating CIN 2+, is preferred when the immediate risk of CIN 3+ is ≥60%, and is acceptable for those with risks between 25% and 60%. Expedited treatment is preferred for nonpregnant patients 25 years or older with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) cytology and concurrent positive testing for HPV genotype 16 (HPV 16) (i.e., HPV 16–positive HSIL cytology) and never or rarely screened patients with HPV-positive HSIL cytology regardless of HPV genotype.

- Shared decision-making should be used when considering expedited treatment, especially for patients with concerns about the potential impact of treatment on pregnancy outcomes.”

- The guideline recommends all positive primary HPV screening tests, regardless of genotype, have an additional reflex triage test performed from the same laboratory specimen (e.g., reflex cytology):

- “Additional testing from the same laboratory specimen is recommended because the findings may inform colposcopy practice. For example, those HPV-16 positive HSIL cytology qualify for expedited treatment.

- HPV 16 or 18 infections have the highest risk for CIN 3 and occult cancer, so additional evaluation (e.g., colposcopy with biopsy) is necessary even when cytology results are negative.

- If HPV 16 or 18 testing is positive, and additional laboratory testing of the same sample is not feasible, the patient should proceed directly to colposcopy.”

- The guideline emphasizes the need to continue surveillance with HPV testing or cotesting at 3-year intervals for at least 25 years after treatment and initial post-treatment management of histologic HSIL, CIN 2, CIN 3, or AIS.

- “Continued surveillance at 3-year intervals beyond 25 years is acceptable for as long as the patient's life expectancy and ability to be screened are not significantly compromised by serious health issues.

- The 2012 guidelines recommended return to 5-year screening intervals and did not specify when screening should cease. New evidence indicates that risk remains elevated for at least 25 years, with no evidence that treated patients ever return to risk levels compatible with 5-year intervals.”

- On the topic of updated management of primary HPV screening, the guideline notes:

- “When primary HPV screening is used, performance of an additional reflex triage test (e.g., reflex cytology) for all positive HPV tests regardless of genotype is preferred (this includes tests positive for genotypes HPV 16/18) (CIII). However, if primary HPV screening test genotyping results are HPV 16 or HPV 18 positive and reflex triage testing from the same laboratory specimen is not feasible, referral for colposcopy before obtaining additional testing is acceptable (CIII). If genotyping for HPV 16 or HPV 18 is positive, and triage testing is not performed before the colposcopy, collection of an additional triage test (e.g., cytology) at the colposcopy visit is recommended (CIII).”

- Because HPV–16 positive and HPV 18–positive test results have the highest risk of CIN 3 and occult cancers, additional diagnostic procedures are recommended for all positive test results (e.g., colposcopy with biopsy for NILM and low-grade cytology and expedited treatment for HSIL cytology that is positive for HPV type 16). This guideline replaces interim guidance (2015) for the management of a positive result for HPV primary screening, which recommended direct referral to colposcopy for HPV test results positive for HPV 16 and/or HPV 18, and performance of cytology for positive results due to other (non-16/18) high-risk HPV types.4 The immediate risk of CIN3+ in patients with HPV 16–positive and HSIL cytology exceeds the treatment threshold of 60%; therefore, these patients should be given the option for expedited treatment without preceding confirmatory biopsy (see Section E.3). Expedited treatment is only possible if cytology is performed. Therefore, reflex cytology is recommended for all HPV-positive primary screening results, regardless of HPV genotype. If reflex testing from the same laboratory specimen as the HPV test is not feasible, patients should proceed directly to colposcopy.4 In this situation, collection of an additional triage test (e.g., cytology) is recommended at the time of colposcopy to provide further information for risk-based management (e.g., if HPV 16–positive HSIL cytology is identified, treatment may be considered even if CIN 2+ is not identified on biopsy). Combining a test with high specificity (e.g., cytology when it is interpreted as HSIL) with a test with high sensitivity (i.e., HPV test) allows more precise, risk-based management of these patients.”

- “Observation is indicated for low-grade cytology results (ASC-US, LSIL), which are likely to represent non-16/18 HPV infections with a high probability for regression and low-risk for rapid progression to cancer.”27

Also in 2019, the ASCCP published guidelines for cervical cancer screening in immunosuppressed women without an HIV infection. The following table was provided by Moscicki, et al. (2019):

Table 3. Summary of Cervical Cancer Screening Recommendations for Non-HIV Immunocompromised Women

| Risk group category |

Recommendation |

| Solid organ transplant |

|

| Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant |

|

| Inflammatory bowel disease on immunosuppressant treatments |

|

| Inflammatory bowel disease not on immunosuppressant treatment |

|

| Systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis on immunosuppressant treatments |

|

| Rheumatoid arthritis not on immunosuppressive treatments |

|

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus |

|

In a 2025 update, the Enduring Consensus Cervical Cancer Screening and Management Guidelines Committee developed recommendations for using self-collected vaginal samples for HPV testing as a cervical cancer screening tool. These guidelines reaffirm the 2019 enduring guidelines and note that there is “high sensitivity and agreement for detection of precancer between self-collected vaginal specimens and clinician-collected cervical specimens for PCR-based HPV assays.”29

The following recommendations address the use of self-collected vaginal specimens for cervical cancer screening. They “apply only to results obtained in asymptomatic, average-risk individuals with a cervix undergoing screening or surveillance.”

- “Clinician-collected cervical specimens are preferred, and self-collected vaginal specimens are acceptable for cervical cancer screening (AII).

- When self-collected vaginal specimens are HPV negative in the screening setting, repeat testing in 3 years is recommended (AII).

- When self-collected vaginal specimens are positive for HPV 16 and/or 18, direct referral for colposcopy with concurrent cytology collection is recommended (AII).

- When self-collected vaginal specimen HPV test results are:

- a) positive for HPV (untyped)

- b) negative for HPV 16/18 and positive for HPV HR12 (other); or

- c) negative for HPV 16/18 and positive for HPV 45, 33/58, 31, 52, 35/39/68, 51 or combinations thereof, obtaining a clinician-collected cervical specimen for cytology or dual stain is recommended.

- Subsequent management of cytology or dual-stain results per management guidelines is recommended (AII).

- When self-collected vaginal specimen HPV test results are positive for HPV types 56/59/66 and no other carcinogenic types, 1 year repeat testing is recommended (AII). If HPV-positive for any HPV type at the 1-year follow-up, colposcopy is recommended (CIII).”29

Society of Gynecologic Oncology, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Cancer Society, American Society of Cytopathology, College of American Pathologists, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology

Since the 2011 joint guidelines issued by the American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology Screening concerning cervical cancer screening, additional reports regarding the use of primary hrHPV testing so that representatives from the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Cancer Society, American Society of Cytopathology, College of American Pathologists, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology convened to issue interim clinical guidance in 2015. In the 2011 statement, primary hrHPV testing was not recommended. The 2015 recommendations include:

- “Because of equivalent or superior effectiveness, primary hrHPV screening can be considered as an alternative to current US cytology-based cervical cancer screening methods. Cytology alone and cotesting remain the screening options specifically recommended in major guidelines.”

- “A negative hrHPV test provides greater reassurance of low CIN3+ risk than a negative cytology result.”

- “Rescreening after a negative primary hrHPV screen should occur no sooner than every 3 years.”

- “Primary hrHPV screening should not be initiated prior to 25 years of age.”

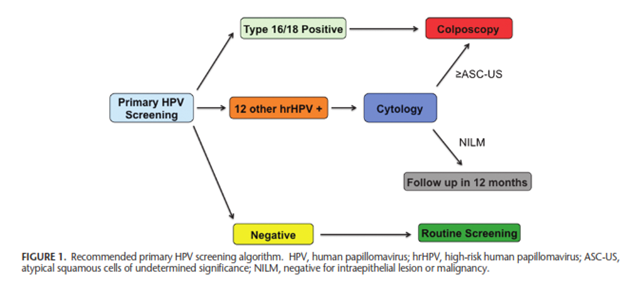

Moreover, they give the following screening algorithm:30

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)

In April 2021, the ACOG released a statement withdrawing and replacing the Practice Bulletin No.168 on cervical cancer screening, stating that it will be joining the ASCCP and the SGO “in endorsing the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) cervical cancer screening recommendations, which replace ACOG Practice Bulletin No.168, Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention, as well as the 2012 ASCCP cervical cancer screening guidelines.” This was reaffirmed in 2023.31

In October 2020, the ACOG released “Updated Guidelines for Management of Cervical Cancer Screening Abnormalities.” These consensus guidelines are based on risk to determine screening, surveillance, colposcopy, or treatment later in life.32 In relation to screening, the updated management guidelines state:

- “Recommendations are based on risk, not results.

- Recommendations of colposcopy, treatment, or surveillance will be based on a patient's risk of CIN 3+ determined by a combination of current results and past history (including unknown history). The same current test results may yield different management recommendations depending on the history of recent past test results.

- Colposcopy can be deferred for certain patients.

- Repeat human papillomavirus (HPV) testing or cotesting at 1 year is recommended for patients with minor screening abnormalities indicating HPV infection with low-risk of underlying CIN 3+ (e.g., HPV-positive, low-grade cytologic abnormalities after a documented negative screening HPV test or cotest).

- All positive primary HPV screening tests, regardless of genotype, should have additional reflex triage testing performed from the same laboratory specimen (eg, reflex cytology).

- Additional testing from the same laboratory specimen is recommended because the findings may inform colposcopy practice. For example, those HPV-16 positive HSIL cytology qualify for expedited treatment.

- HPV 16 or 18 infections have the highest risk for CIN 3 and occult cancer, so additional evaluation (e.g., colposcopy with biopsy) is necessary even when cytology results are negative.

- If HPV 16 or 18 testing is positive, and additional laboratory testing of the same sample is not feasible, the patient should proceed directly to colposcopy.

- Continued surveillance with HPV testing or cotesting at 3-year intervals for at least 25 years is recommended after treatment and initial post-treatment management of histologic HSIL, CIN 2, CIN 3, or AIS. Continued surveillance at 3-year intervals beyond 25 years is acceptable for as long as the patient's life expectancy and ability to be screened are not significantly compromised by serious health issues.

- New evidence indicates that risk remains elevated for at least 25 years, with no evidence that treated patients ever return to risk levels compatible with 5-year intervals.

- Surveillance with cytology alone is acceptable only if testing with HPV or cotesting is not feasible. Cytology is less sensitive than HPV testing for detection of precancer and is therefore recommended more often. Cytology is recommended at 6-month intervals when HPV testing or cotesting is recommended annually. Cytology is recommended annually when 3-year intervals are recommended for HPV or cotesting.

- Human papilloma virus assays that are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for screening should be used for management according to their regulatory approval in the United States. (Note: all HPV testing in [the guidelines] refers to testing for high-risk HPV types only).

- For all management indications, HPV mRNA and HPV DNA tests without FDA approval for primary screening alone should only be used as a cotest with cytology, unless sufficient, rigorous data are available to support use of these particular tests in management.”32

European AIDS Clinical Society

The EASC recommends cervical cancer screening (PAP smear or liquid-based cervical cytology test) for women over 21 years of age every one to three years. Additionally, the EASC notes “HPV genotype testing may aid PAP/liquid-based cervical screening.”33

United States Department of Health and Human Services

The US HHS guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV recommend the following cervical cancer screening:

- “Women with HIV Aged <30 Years:

- WWH aged 21 to 29 years should have a Pap test following initial diagnosis of HIV.

- Pap test should be done at baseline and every 12 months (BII).

- If the results of three consecutive Pap tests are normal, follow-up Pap tests can be performed every 3 years (BII).

- Co-testing (Pap test and HPV test) is not recommended for women younger than 30 years.

- Women with HIV Aged ≥30 Years:

- Pap Testing Only

- Pap test should be done at baseline and every 12 months (BII).

- If results of three consecutive Pap tests are normal, follow-up Pap tests can be performed every 3 years (BII). Or

- Pap Test and HPV Co-Testing

- Pap test and HPV co-testing should be done at baseline (BII).

- If result of the Pap test is normal and HPV co-testing is negative, follow-up Pap test and HPV co-testing can be performed every 3 years (BII).

- If the result of the Pap test is normal but HPV co-testing is positive: Either:

- Follow-up test with Pap test and HPV co-testing should be performed in 1 year.

- If the 1-year follow-up Pap test is abnormal, or HPV co-testing is positive, referral to colposcopy is recommended. Or:

- Perform HPV genotyping.

- If positive for HPV-16 or HPV-18, colposcopy is recommended.

- If negative for HPV-16 and HPV-18, repeat co-test in 1 year is recommended. If the follow-up HPV test is positive or Pap test is abnormal, colposcopy is recommended: Or:

- Pap Test and HPV16 or HPV16/18 Specified in Co-Testing

- Pap test and HPV 16 or 16/18 co-testing should be done at baseline (BII).

- If result of the Pap test is normal, and HPV 16 or 16/18 co-testing is negative, follow-up Pap test and HPV co-testing can be performed every 3 years (BII).

- If initial test or follow-up test is positive for HPV 16 or 16/18, referral to colposcopy is recommended (BII).

- Pap Testing Only

- Primary HPV testing is not recommended (CIII).”34

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The CDC published guidelines concerning HPV testing in cervical cancer screening. “When primary HPV testing is used for screening, cytology testing should be performed for all positive HPV test results to help determine the next steps in management. Ideally, cytology testing should be performed by the laboratory as a reflex test from the same specimen, so the individual does not need to return to the clinic. HPV 16 and 18 are the highest risk HPV type. If the HPV type is not HPV 16 or 18, and the cytology test is normal, returning in one year is recommended. Negative HPV testing or cotesting is less likely to miss disease than normal cytology testing alone. Therefore, cytology testing is recommended more often than HPV testing or cotesting for follow-up of abnormal results. Specifically, cytology testing is recommended annually when HPV testing or cotesting is recommended at three-year intervals, and cytology testing is recommended at six month intervals when HPV testing or cotesting is recommended annually. Annual cervical cancer screening is not recommended for persons at average risk. Instead, cytology testing is recommended every 3 years for persons aged 21–29 years. For persons aged 30–65 years, a cytology test every 3 years, an HPV test alone every 5 years, or a cytology test plus an HPV test (cotest) every 5 years is recommended.”35

American Academy of Family Physicians

The AAFP has published Choosing Wisely Recommendations for low-risk HPV testing. This recommendation states the following: “Don’t perform low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) testing.”

AAFP provides the following rationale and comments pertaining to this recommendation: “National guidelines provide for HPV testing in patients with certain abnormal Pap smears and in other select clinical indications. The presence of high-risk HPV leads to more frequent examination or more aggressive investigation (e.g., colposcopy and biopsy). There is no medical indication for low-risk HPV testing (HPV types that cause genital warts or very minor cell changes on the cervix) because the infection is not associated with disease progression and there is no treatment or therapy change indicated when low-risk HPV is identified.”36

American Society for Clinical Oncology

Resource-stratified recommendations were released in 2022 from the American Society for Clinical Oncology.

For maximal-based resource settings:

- “1.1. In maximal-resource settings, cervical cancer screening with HPV DNA testing should be offered every 5 years from age 25 to 65 years (either self- or clinician-collected). On an individual basis, women may elect to receive screening until age 70 years.

- 1.2. Women who are ≥ 65 years of age who have had consistently negative screening results during past ≥ 15 years may cease screening. Women who are 65 years of age and have a positive result after age 60 should be reinvited to undergo screening 2, 5, and 10 years after the last positive result. If women have received no or irregular screening, they should undergo screening once at 65 years of age, and if the result is negative, exit screening.

- 1.3. If the results of the HPV DNA test are positive, clinicians should then perform triage with reflex genotyping for HPV 16/18 (with or without HPV 45) and/or cytology as soon as HPV test results are known.

- 1.4. If triage results are abnormal (ie, ≥ ASC-US or positive for HPV 16/18 [with or without HPV 45]), women should be referred to colposcopy, during which biopsies of any acetowhite (or suggestive of cancer) areas should be taken, even if the acetowhite lesion might appear insignificant. If triage results are negative (e.g., primary HPV positive and cytology triage negative), then repeat HPV testing at the 12-month follow-up.

- 1.5. If HPV test results are positive at the repeat 12-month follow-up, refer women to colposcopy. If HPV test results are negative at the 12- and 24-month follow-up or negative at any consecutive HPV test 12 months apart, then women should return to routine screening.

- 1.6. Women who have received HPV and cytology co-testing triage and have HPV-positive results and abnormal cytology should be referred for colposcopy and biopsy. If results are HPV positive and cytology normal, repeat co-testing at 12 months. If at repeat testing HPV is still positive, patients should be referred for colposcopy and biopsy, regardless of cytology results.

- 1.7. If the results of the biopsy indicate that women have precursor lesions (CIN2+), then clinicians should offer loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP; if there is a high level of quality assurance [QA]) or, where LEEP is contraindicated, ablative treatments may be offered.

- 1.8. After women receive treatment for precursor lesions, follow-up should consist of HPV DNA testing at 12 months. If 12-month results are positive, continue annual screening; if not, return to routine screening.”37

In enhanced-resource settings:

- “2.1. In enhanced-resource settings, cervical cancer screening with HPV DNA testing should be offered to women age 30-65 years, every 5 years (i.e., second screen 5 years from the first) (either self- or clinician-collected).

- 2.2. If there are two consecutive negative screening test results, subsequent screening should be extended to every 10 years.

- 2.3. Women who are ≥ 65 years of age who have had consistently negative screening results during past ≥ 15 years may cease screening. Women who are 65 years of age and have a positive result after age 60 should be reinvited to undergo screening 2, 5, and 10 years after the last positive result. If women have received no or irregular screening, they should undergo screening once at 65 years of age, and if the result is negative, exit screening.

- 2.4. If the results of the HPV DNA test are positive, clinicians should then perform triage with HPV genotyping for HPV 16/18 (with or without HPV 45) and/or reflex cytology.

- 2.5. If triage results are abnormal (ie, ≥ASC-US or positive for HPV 16/18 [with or without HPV 45]), women should be referred to colposcopy, during which biopsies of any acetowhite (or suggestive of cancer) areas should be taken, even if the acetowhite lesion might appear insignificant. If triage results are negative (e.g., primary HPV positive and cytology triage negative), then repeat HPV testing at the 12-month follow-up.

- 2.6. If HPV test results are positive at the repeat 12-month follow-up, refer women to colposcopy. If HPV test results are negative at the 12- and 24-month follow-up or negative at any consecutive HPV test 12 months apart, then women should return to routine screening.

- 2.7. If the results of colposcopy and biopsy indicate that women have precursor lesions (CIN2+), then clinicians should offer LEEP (if there is a high level of QA) or, where LEEP is contradicted, ablative treatments may be offered.

- 2.8. After women receive treatment for precursor lesions, follow-up should consist of HPV DNA testing at 12 months. If 12-month results are positive, continue annual screening; if not, return to routine screening.”37

In limited settings:

- “3.1. In limited settings, cervical cancer screening with HPV DNA testing should be offered to women 30 to 49 years of age every 10 years, corresponding to 2 to 3 times per lifetime (either self- or clinician-collected).

- 3.2. If the results of the HPV DNA test are positive, clinicians should then perform triage with reflex cytology (quality assured) and/or HPV genotyping for HPV 16/18 (with or without HPV 45) or with VIA. If institutions are currently using reflex cytology, they should transition from cytology to HPV genotyping.

- 3.3. If cytology triage results are abnormal (i.e. ≥ atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance [ASC-US]), women should be referred to quality assured colposcopy (the first choice, if available and accessible for women who are ineligible for thermal ablation), during which biopsies of any acetowhite (or suggestive of cancer) areas should be taken, even if the acetowhite lesion might appear insignificant. If colposcopy is not available, then perform VAT.

- 3.4. If HPV genotyping or VIA or VAT triage results are positive, then women should be treated. If the results from these forms of triage are negative, then repeat HPV testing at the 12-month follow-up.

- 3.5. If test results are positive at the repeat 12-month follow-up, then women should be treated.

- 3.6. For treatment, clinicians should offer ablation if the criteria are satisfied; if not and resources available, then offer LEEP.

- 3.7. After women receive treatment for precursor lesions, follow-up should consist of the same testing at 12 months.”37

Finally, in basic settings:

- “4.1. Health systems in basic settings should move to population-based screening with HPV testing at the earliest opportunity (either self- or clinician-collected). If HPV DNA testing for cervical cancer screening is not available, then VIA should be offered with the goal of developing health systems. Screening should be offered to women 30 to 49 years of age, at least every 10 years (increasing the frequency to every 5 years, resources permitting).

- 4.2. If the results of available HPV testing are positive, clinicians should then perform VAT followed by treatment with thermal ablation and/or LEEP, depending on the size and location of the lesion.

- 4.3. If primary screening is VIA and results are positive, then treatment should be offered with thermal ablation and/or LEEP, depending on the size and location of the lesion.

- 4.4. After women receive treatment for precursor lesions, then follow-up with the available test at 12 months. If the result is negative, then women return to routine screening.”37

References:

1. Feldman S, Goodman A, Peipert J. Screening for cervical cancer in resource-rich settings. Updated January 29, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-cervical-cancer-in-resource-rich-settings

2. Feldman S, Crum C. Cervical cancer screening tests: Techniques for cervical cytology and human papillomavirus testing. Updated October 30, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cervical-cancer-screening-tests-techniques-for-cervical-cytology-and-human-papillomavirus-testing

3. ACS. Key Statistics for Cervical Cancer. American Cancer Society, Inc. Updated January 16, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

4. William R Robinson. Screening for Cervical Cancer in Resource-Risk Settings. Updated Januray 9,2025 https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-cervical-cancer-in-resource-rich-settings

5. Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. Sep 2020;70(5):321-346. doi:10.3322/caac.21628

6. William R Robinson. Screening for cervical cancer in patients with HIV infection and other immunocompromised states. Updated October 4, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-cervical-cancer-in-patients-with-hiv-infection-and-other-immunocompromised-states

7. Health T. Teal WandTM for At-Home Cervical Cancer Screening. https://www.getteal.com/teal-wand

8. Crane L, Jennings A, Fitzpatrick MB, et al. Experiences and Preferences Reported with an At-Home Self-Collection Device Compared with In-Clinic Speculum-Based Cervical Cancer Screening in the United States. Women's Health Reports. 2025/01/01 2025;6(1):564-575. doi:10.1089/whr.2025.0017

9. Marchand L, Mundt M, Klein G, Agarwal SC. Optimal collection technique and devices for a quality pap smear. WMJ : official publication of the State Medical Society of Wisconsin. Aug 2005;104(6):51-5.

10. Mendez K, Romaguera J, Ortiz AP, Lopez M, Steinau M, Unger ER. Urine-based human papillomavirus DNA testing as a screening tool for cervical cancer in high-risk women. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. Feb 2014;124(2):151-5. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.07.036

11. Pathak N, Dodds J, Zamora J, Khan K. Accuracy of urinary human papillomavirus testing for presence of cervical HPV: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). Sep 16 2014;349:g5264. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5264

12. NCI. Cervical Cancer Screening (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. National Institutes of Health. Updated April 21, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/hp/cervical-screening-pdq

13. Sabeena S, Kuriakose S, Binesh D, et al. The Utility of Urine-Based Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening in Low-Resource Settings. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. Aug 1 2019;20(8):2409-2413. doi:10.31557/apjcp.2019.20.8.2409

14. NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines(R)) - Cervical Cancer Version 3.2025. Updated February 10, 2025. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf

15. Sasieni P, Castanon A, Cuzick J. Screening and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. International journal of cancer. Aug 1 2009;125(3):525-9. doi:10.1002/ijc.24410

16. Dahlstrom LA, Ylitalo N, Sundstrom K, et al. Prospective study of human papillomavirus and risk of cervical adenocarcinoma. International journal of cancer. Oct 15 2010;127(8):1923-30. doi:10.1002/ijc.25408

17. Chen HC, Schiffman M, Lin CY, et al. Persistence of type-specific human papillomavirus infection and increased long-term risk of cervical cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Sep 21 2011;103(18):1387-96. doi:10.1093/jnci/djr283

18. Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of Screening With Primary Cervical HPV Testing vs Cytology Testing on High-grade Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia at 48 Months: The HPV FOCAL Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. Jul 3 2018;320(1):43-52. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7464

19. Massad LS. Replacing the Pap Test With Screening Based on Human Papillomavirus Assays. Jama. Jul 3 2018;320(1):35-37. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7911

20. Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, Senger CA, Durbin S, Weyrich MS. Screening for Cervical Cancer With High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Testing: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama. Aug 21 2018;320(7):687-705. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10400

21. Bonde JH, Sandri MT, Gary DS, Andrews JC. Clinical Utility of Human Papillomavirus Genotyping in Cervical Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Jan 2020;24(1):1-13. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000494

22. Pry JM, Manasyan A, Kapambwe S, et al. Cervical cancer screening outcomes in Zambia, 2010-19: a cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. Jun 2021;9(6):e832-e840. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00062-0

23. Dilley S, Huh W, Blechter B, Rositch AF. It's time to re-evaluate cervical Cancer screening after age 65. Gynecol Oncol. Jul 2021;162(1):200-202. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.04.027

24. Qin J, Holt HK, Richards TB, Saraiya M, Sawaya GF. Use Trends and Recent Expenditures for Cervical Cancer Screening-Associated Services in Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries Older Than 65 Years. JAMA Intern Med. Jan 1 2023;183(1):11-20. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.5261

25. Winer RL, Lin J, Anderson ML, et al. Strategies to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening With Mailed Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling Kits: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. Nov 28 2023;330(20):1971-1981. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.21471

26. USPSTF. Screening for Cervical Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation StatementUSPSTF Recommendation: Screening for Cervical CancerUSPSTF Recommendation: Screening for Cervical Cancer. Jama. 2018;320(7):674-686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897

27. Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Apr 2020;24(2):102-131. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000525

28. Moscicki AB, Flowers L, Huchko MJ, et al. Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening in Immunosuppressed Women Without HIV Infection. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Apr 2019;23(2):87-101. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000468

29. Wentzensen N, Massad LS, Clarke MA, et al. Self-Collected Vaginal Specimens for HPV Testing: Recommendations From the Enduring Consensus Cervical Cancer Screening and Management Guidelines Committee. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Apr 1 2025;29(2):144-152. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000885

30. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Apr 2015;19(2):91-6. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000103

31. ACOG. Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. Updated April 12, 2021. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2021/04/updated-cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines

32. ACOG. Updated Guidelines for Management of Cervical Cancer Screening Abnormalities. Updated October 9, 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/10/updated-guidelines-for-management-of-cervical-cancer-screening-abnormalities

33. EASC. Guidlines Version 12.0. https://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs-guidelines/

34. HHS. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV. Updated July 9, 2024. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/human

35. CDC. HPV-Associated Cancers and Precancers. Updated July 22, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/hpv-cancer.htm

36. AAFP. Choosing Wisely Recommendations. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/collections/choosing-wisely/28.html

37. Shastri SS, Temin S, Almonte M, et al. Secondary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: ASCO Resource-Stratified Guideline Update. JCO Glob Oncol. Sep 2022;8:e2200217. doi:10.1200/GO.22.00217

38. FDA. BD ONCLARITY HPV ASSAY. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/devicesatfda/index.cfm?db=pma&id=391601

39. FDA. PMA Monthly approvals from 7/1/2018 to 7/31/2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?ID=409848

40. Rice SL, Editor. Cobas HPV test approved for first-line screening using SurePath preservative fluid. CAP Today. August 2018.

41. FDA. Cobas HPV For Use On The Cobas 6800/8800 Systems. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/devicesatfda/index.cfm?db=pma&id=448383

Coding Section

| Code |

Number |

Description |

| CPT |

87623 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Human Papillomavirus (HPV), low-risk types (e.g., 6, 11, 42, 43, 44) |

|

|

87624 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Human Papillomavirus (HPV), high-risk types (e.g., 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) |

|

|

87625 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Human Papillomavirus (HPV), types 16 and 18 only, includes type 45, if performed |

| 87626 (effective 01/01/2025) | Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); Human Papillomavirus (HPV), separately reported high-risk types (EG, 16, 18, 31, 45, 51, 52) and high-risk pooled result(s) | |

|

|

88141 |

Cytopathology, cervical or vaginal (any reporting system), requiring interpretation by physician |

|

|

88142 |

Cytopathology, cervical or vaginal (any reporting system), collected in preservative fluid, automated thin layer preparation; manual screening under physician supervision |

|

|

88143 |

Cytopathology, cervical or vaginal (any reporting system), collected in preservative fluid, automated thin layer preparation; with manual screening and rescreening under physician supervision |

|

|

88147 |

Cytopathology smears, cervical or vaginal; screening by automated system under physician supervision |

|

|

88148 |

Cytopathology smears, cervical or vaginal; screening by automated system with manual rescreening under physician supervision |

|

|

88150 |

Cytopathology, slides, cervical or vaginal; manual screening under physician supervision |

|

|

88152 |

Cytopathology, slides, cervical or vaginal; with manual screening and computer-assisted rescreening under physician supervision |

|

|

88153 |

Cytopathology, slides, cervical or vaginal; with manual screening and rescreening under physician supervision |

|

|

88164 |

Cytopathology, slides, cervical or vaginal (the bethesda system); manual screening under physician supervision |

|

|

88165 |

Cytopathology, slides, cervical or vaginal (the bethesda system); with manual screening and rescreening under physician supervision |

|

|

88166 |

Cytopathology, slides, cervical or vaginal (the bethesda system); with manual screening and computer-assisted rescreening under physician supervision |

|

|

88167 |

Cytopathology, slides, cervical or vaginal (the bethesda system); with manual screening and computer-assisted rescreening using cell selection and review under physician supervision |

|

|

88174 |

Cytopathology, cervical or vaginal (any reporting system), collected in preservative fluid, automated thin layer preparation; screening by automated system, under physician supervision |

|

|

88175 |

Cytopathology, cervical or vaginal (any reporting system), collected in preservative fluid, automated thin layer preparation; with screening by automated system and manual rescreening or review, under physician supervision |

| 0502U (effective 10/01/2024) | Human papillomavirus (HPV), E6/E7 markers for high-risk types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68), cervical cells, branched-chain capture hybridization, reported as negative or positive for high risk for HPV | |

|

|

G0123 |

Screening cytopathology, cervical or vaginal (any reporting system), collected in preservative fluid, automated thin layer preparation, screening by cytotechnologist under physician supervision |

|

|

G0124 |

Screening cytopathology, cervical or vaginal (any reporting system), collected in preservative fluid, automated thin layer preparation, requiring interpretation by physician |

|

|

G0141 |

Screening cytopathology smears, cervical or vaginal, performed by automated system, with manual rescreening, requiring interpretation by physician |

|

|

G0143 |